You just don’t hear much about grief until it’s upon you.

We just don’t talk much about grief in this culture. Talking too much about our own deaths is considered morbid. Asking someone what their grief is like seems insensitive. Telling someone too much about your own grief can make you worry you’re being a downer. But for all these reasons, we don’t really know what we’re getting into when grief suddenly hits us. Then, we need to know what is ahead of us. We need a roadmap to the rest of our lives. So here is what I have learned about grief, in case it is helpful to you.

Grief is Not an Emotion

This is actually something I only learned recently from an interview with Cole Imperi (Thanatologist) with Alie Ward on her “ologies” podcast.

Grief is not an emotion. It is a response to loss. It is a process that allows us to come to terms with our loss. There are six aspects of grief: emotional, social, spiritual, cognitive, physical, and behavioural. You may have more experiences in some of these categories than others. Everyone experiences grief differently. In fact, if you had a certain combination of grief symptoms in the past, and then experience a new loss, your grief might come out in a different way than the first time. As we change over time, so do our responses to grief.

I hope the above definition helps people be less judgmental of their responses to grief. I used to judge myself for the way I was feeling at any given moment. If I hadn’t felt particularly emotional on a certain day, or if someone else seemed to be having more trouble functioning than I was. I would think, “If my family member can’t even shower, but I’m able to get up, care for my child, and feel okay sometimes, does that mean I didn’t love Jake enough? Did my family member love Jake more than I did?” That sounded crazy even to me at the time, but the feelings of worry and self-judgement were real. It turns out, we were all just experiencing grief in our own way. There is no right way to do grief, and it doesn’t even express as an emotion all the time. It might come out in foggy thinking, or even dry lips and gastrointestinal issues. Cole Imperi has a book coming out some time in the next year and I can’t wait to find out more.

Click here for the podcast.

The “Stages” of Grief

The Stages of Grief, as defined by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, were originally about the emotional challenges of people approaching their own deaths. See the video below for my favourite example:

Later, it was generalized to people who were grieving for others. We do tend to feel all those feelings (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance), but not in any specific order, and we can jump back and forth repeatedly. The CBC radio program, Tapestry, did an interesting segment with psychologist David Feldman on the “stages” of grief. You can listen to it here, but I have also given some of the information below.

There are several common feelings associated with grief that are missing from the well-known stages: Yearning, Relief, and Guilt.

Yearning

Yearning is such an intense part of grief. Sometimes you need the person so badly it feels like there should be a way to be with them again. Feldman says you yearn for the person you lost, the person they would have been as they got older, and the role you played in their lives. I used to feel pulled toward Heaven to be with Jake, and kind of wish that I would die in an accident. I would imagine accidentally falling down long stairways, or my car veering off the road into something. I calmly explained to my sister, “I’m not suicidal, I just have a death wish.” She pointed out that many tragic superheroes have the same kind of feeling. It’s what makes them so fearless in battle. Of course, I also had my daughter here on Earth. I felt pulled in both directions, and decided to believe that Jake was being well-taken care-of in Heaven, and that Earth was the more challenging place to be, which was why Robin, and the other people I cared about, needed me more.

I don’t have a death-wish anymore. As time progressed, life didn’t feel as difficult and I started to find joy and meaning in living. However, there are still times when I get to be alone at Jake’s grave, and the deep grief and yearning feelings descend on me. Suddenly the time-span of my life seems so incredibly long again, but even in the moment, I know that feeling will eventually pass. At the very least, when it is my time to die, I’ll have something to look forward to.

Relief

Relief is a normal feeling, especially after a long illness or when your role as caregiver is over. I can’t speak much to this, personally, as Jake’s illness was not prolonged. Click here for a good website that explains relief after a death, in detail. Basically, you must remember that the relief you feel about an end to suffering or overwhelming care tasks, doesn’t negate the other very real feelings of grief.

Guilt

I remember my dad telling me once, “Everyone feels guilty after a death. If you think you could have played a part in preventing it, you feel guilty. If you had nothing to do with the death, you still feel guilty, perhaps about not spending enough time with the person. You can always find something to feel guilty about.” It sounded so strange, but I found myself repeating that wisdom to other people, over time. After Jake died, Rich and I both felt incredibly guilty. Rich worried he somehow brought germs or bacteria back from his recent trip. I felt, as Jake’s mother, I should have known better than the doctors, when they said he wasn’t that sick. Our brains were trying to solve a problem that it was too late to solve. I also felt guilty whenever I felt happy or normal or momentarily wasn’t thinking about Jake – as if not thinking of him was disloyal and would cause him to be even more lost to us. I felt like, since he wasn’t physically present, I had to make sure I was thinking of him all the time, to keep a place for him where he should be. But you can’t think about anything 100% of the time. And you can’t feel sad all the time either. Feldman even argues that denial is not a bad thing. As stated above, grief is a process, with the purpose of letting you eventually come to terms with a loss. Just like medicine, it is good for us in specific doses. The feelings of denial are actually your brain giving you a much needed break. So if you are grieving, and you wake up one morning feeling normal. Instead of feeling guilty, you can thank your brain for giving you that break, knowing the feelings will be back later. Or go ahead and feel guilty. It’s normal. It doesn’t mean you are actually doing anything wrong.

Accepting Your Feelings

I remember my grief counsellor telling me that once you become an expert at grief, you get good at accepting your feelings. This is because you have had so much experience with your feelings going up and down unpredictably, that you realize each of them will pass on their own. There’s nothing you have to do or judge about them. They are just feelings. My husband and I found that sometimes we felt sad at moments when most people would be happy. Other times we felt happy when people would have expected us to be sad. When you are grieving, even more than at other times, you can’t predict or fully control your emotions, so you eventually come to accept them. It’s good practice for accepting your feelings for the rest of your life.

Grief Triggers Lesson with Exposure

In the first year of grief, almost every experience, without your loved-one, is new. In my first year, every experience felt heart-wrenching; Eating breakfast, bathing my child, going to the grocery store. Every moment took bravery. But thankfully, our brains eventually acclimatize to each situation. If we can get through it enough times, it will start to feel routine again (and meanwhile, if you ask someone who works at the grocery store, you can go to the employees only section to cry).

Things can start to feel so routine, that you forget how much a new trigger can get to you. After four years of grief, I thought I was coping really well, until I went to Canada’s Wonderland with my husband’s side of the family. It wasn’t until I arrived that I realized I hadn’t been there since the week after Jake’s funeral, when I had gone with the exact same people, for the exact same reason (that Rich’s niece and nephews were visiting from BC). I had an intense grief reaction and just wanted to get away. I ended up leaving the group, buying a cooler, and walking around Canada’s Wonderland, drinking, crying, and talking to my sister on the phone. I definitely felt like a crazy lady. After I calmed down, I went back to the group and bravely took my kids on a bunch of rides. I felt much calmer by the end, but wasn’t sure I wanted to go back any time soon. It was an interesting reminder of how much my brain had acclimatized to everyday life, without my actual grief having to change. It had been four years, but it was a brand new kind of trigger. It made me really appreciate how much my brain had done for me, by getting used to the rest of life. And I knew that if it was important to me to enjoy Canada’s Wonderland, all I had to do was go there a lot more. Maybe with my own friends and no kids, to create some different memories.

Grief Triggers are Seasonal

One piece of information I found most helpful, from my first session with a grief counsellor, was that grief triggers change with the seasons. The start of every season is the most challenging because there are all sorts of new things to get used to seeing and doing without your loved one. By the end of the season, your brain acclimatizes somewhat. Unfortunately, then the next season starts, and you have to acclimatize all over again (get used to Halloween, and it’s on to Christmas). I asked my counsellor when I would enjoy Christmas again and she said it would take about 3-5 Christmases. And that didn’t count the ones we didn’t celebrate because of grief. I found it took about four Christmases to actually enjoy the site of Christmas lights. I still don’t enjoy anticipating Christmas, but I have found that I always enjoy the actual day more than I expect to, because it’s hard not to enjoy seeing family, eating good food, and watching my children open presents.

Significant Dates

I have heard from many people that anticipating events, like a significant anniversary or birthday, can feel worse than the actual day/event itself. Rich and I have found this to be true as well. Often the week leading up to Jake’s death anniversary is the hardest time.

I also get a lot of comfort, on the day, from posting on social media. It allows me to tell the world what that day means to me, then spend other parts of the day reading comments, as the love pours in. Having so many people acknowledge our loss, and getting a day to devote to honouring Jake and our grief, actually feels quite healing.

Cocooning

At my first grief counselling session, my therapist warned me about something called “Cocooning.” She said that when your loved-one first dies, your brain protects you from the immediate impact of the trauma by numbing your emotions. It may not feel like it, but it does. People may say you are coping surprisingly well. You may want to talk about what happened with all sorts of people. But around five weeks to three months in, you go into a cocooning phase. You’re not in shock anymore. Everything that can be said has been said. It becomes harder to go out and be around other people. It can look a lot like depression and last a few months. I remember when this phase hit us. People made us offers to socialize and we just didn’t want to. We didn’t feel like being around happy people. We didn’t feel like acting happier than we were. But we also didn’t feel like going out and talking about our sadness either. We had already said it all. Everything seemed pointless. The world seemed irritating and overwhelming. I remember saying to Rich once, “I hate everybody except us.” It helped to know that this was a phase. I could explain it to my friends and family and know that we didn’t need medication to fix it. We would eventually come out of it. And we did. I haven’t been able to find a lot about this phenomenon the internet, and my therapist has since retired. It could be that this is a phenomenon more common for sudden, traumatic losses. But I thought I should put it in, in case it is helpful to anyone else.

Emptying Your Bucket

Grief emotions can build up over a period of time, like a bucket slowly filling with water. You can hold in your emotions for a while, when you are in the middle of other things, but there will come a point when your bucket is about to overflow and you need to empty it, by letting your emotions out. My husband and I found this analogy helpful when communicating with each other. We could be in the middle of an amusement park with the kids and one of us would say, “I have to go empty my bucket” and find a quiet place to cry. Sometimes people would say something that made me cry and they would feel guilty about it, but I would explain that I had actually really needed to empty my bucket and it was a relief to let it out.

What Will People Think?

I have some social anxiety. I can be the life of the party, then spend the next few days worrying what people thought of me. After Jake died, my social anxiety kicked in as well. I used to worry that if I looked too happy, people would think I didn’t really miss Jake. I worried that I wouldn’t cry at the visitation and people would judge me. My family assured me that not everyone cries at visitations and that people were relieved to see that I could have some happy times and that no one thought, at any point, that I didn’t miss Jake. It was reassuring to keep this in mind.

There is No Social Script for What to Say to Someone Who is Grieving

“My condolences,” and, “I’m sorry for your loss,” only get us so far. Most people don’t know what to say to someone who is grieving for fear of making it worse. If the grieving person seems happy, no one wants to bring their mood down by mentioning anything triggering. But, this can often make the grieving person feel like others are forgetting their loved-one. If the grieving person is crying, people often want to make them feel better, but may not realize that the person’s bucket was full and they really needed to have a good cry. And the trouble is, comforters often say what makes themselves feel better about the person’s situation and the unpredictability of the world. For example, “Everything happens for a reason,” or “Something worse would have happened to him if he hadn’t died then,” (yes, a stranger once said this to me after he complimented Robin’s blue eyes and I told him about Jake’s blue eyes). I’ve also gotten, “It was just his time.” We can’t help but feel annoyed when people say things that are so far from our own experiences or beliefs. But we can remember, cognitively, if not emotionally, that these well-meaning people are just clueless, not heartless. We don’t want them to have to go through our pain, to truly understand it. And honestly, I still sometimes put my foot in my mouth when dealing with other grieving people! I often like to tell people who are grieving that I understand grief because my son died. But I talked to another mom who lost a baby and she found it an extra burden to hear about the losses of so many other people. People are all different and we can’t get it right every time, but we can try to have compassion for ourselves and others as we all muddle through.

So what do we say?

When I was grieving and trying to figure out what I believed about where Jake was and what he was experiencing, I appreciated being able to talk through theories with people, but I didn’t like when people tried to confidently tell me where Jake’s spirit was now. My sister’s words meant the most to me when she said, “I’ll believe what you believe. You’re Jake’s mom and you know him best.” Not everyone can make this statement honestly, but it really helped to legitimize what I was trying to do. Now, when I meet people who are grieving and I want to get spiritual about it, I usually say, “Do you believe anything about an afterlife?” and let their beliefs take priority. I also sometimes check in with people about a conversation if I’m not sure it went right, like, “Was that okay that I asked ___ about your son?” Cole Imperi, from the podcast, above, recommended asking, “How is your grief today?” instead of “How are you?” I never knew how to answer, “How are you?” while I was grieving. I had another friend who said, “I’m just going to treat you like normal unless you tell me to do otherwise.” I liked that.

If you are the support person for a grieving person: I have found that when someone is having a hard time, deciding how someone else can help can be too much cognitive load. People often feel guilty making specific requests. When we say, “Let me know if there’s anything I can do,” we’re usually serious, but we are unlikely to be taken up on that offer. Try just showing up with food, or making specific offers like, “Can I walk your dog this week?” My friend arranged for people to sign up online to bring us food. This format was both helpful and required nothing from us.

If you are the grieving person: Consider making your wishes clear. It may be a huge relief to your family and friends to know what you need: “E.g. I would like people to still talk about my loved-one,” “Can you check in on me now and then this week?” “I can’t stand being alone for breakfast. Can anyone have me over for breakfast this week?”

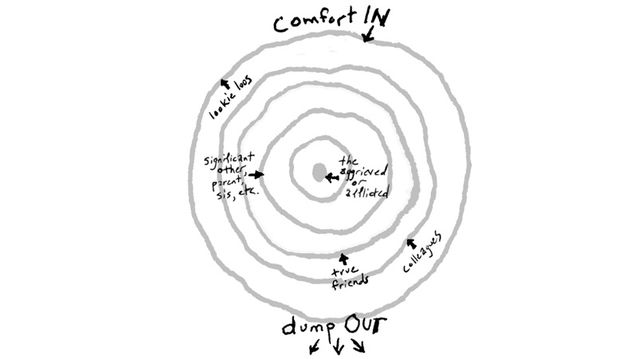

The Ring Theory of Venting

Chances are, if you are a support person for someone who is grieving, you are probably grieving that same loss yourself. If you were not close enough to the person who died to be specifically grieving that loss, it might make you think of other losses in your life, or losses that could happen, and bring up a lot of emotions. Even seeing the person you care about in pain is difficult. The person in the center of the crisis vents to you, but what do you say back to them? And who do you tell about your feelings? Click on the picture below for an explanation of the Ring Theory. I think if we all followed this advice, fewer people would end up with hurt feelings.

Can I Ever Be Happy Again?

When I found out Jake was going to die, I called my sister’s friend, Lynne, who was the only person I knew who had lost a child. My first question was, “Can I ever be happy again?” She said, “You absolutely can be happy again.” Her advice from her therapist was to give it five years. That still seemed like a depressingly long time. But, I found that even within those five years, I was gradually able to enjoy more and more of what life had to offer. Grief comes in waves, and when it wasn’t a grief moment, life could still feel sweet. I learned not to rate my overall life satisfaction, but to take life moment by moment.

David Feldman stated that although it’s never “okay” that the person is gone, grief softens with time. It’s not that you will never miss the person, but you can re-engage in your life and smile again.

Conclusion

Grief is a universal human experience. If we could not forge through grief, we never would have survived as a species. Cole Imperi says that we already have everything inside ourselves that we need to heal. I find a good counsellor is an invaluable resource as well. If you are currently in the process of grieving, I’m so sorry for your loss. Try to be kind to yourself as you go through this process. I wish you didn’t have to.

Grief Triggers are Seasonal

Cocooning

Grief Triggers are Lessened with Exposure – grocery stores, Wonderland, little boys, babies, twins

Longing and Guilt should be part of the “Stages of Grief”

Emptying Your Bucket

Accepting Your Emotions

There is No Social Script for Grief

“Can I Ever Be Happy Again?”

Visit the Jacob Hillerby Memorial Bursary at Renison College by Clicking Here.

Get Jacquify delivered to your inbox.

Web Design by LMG, email